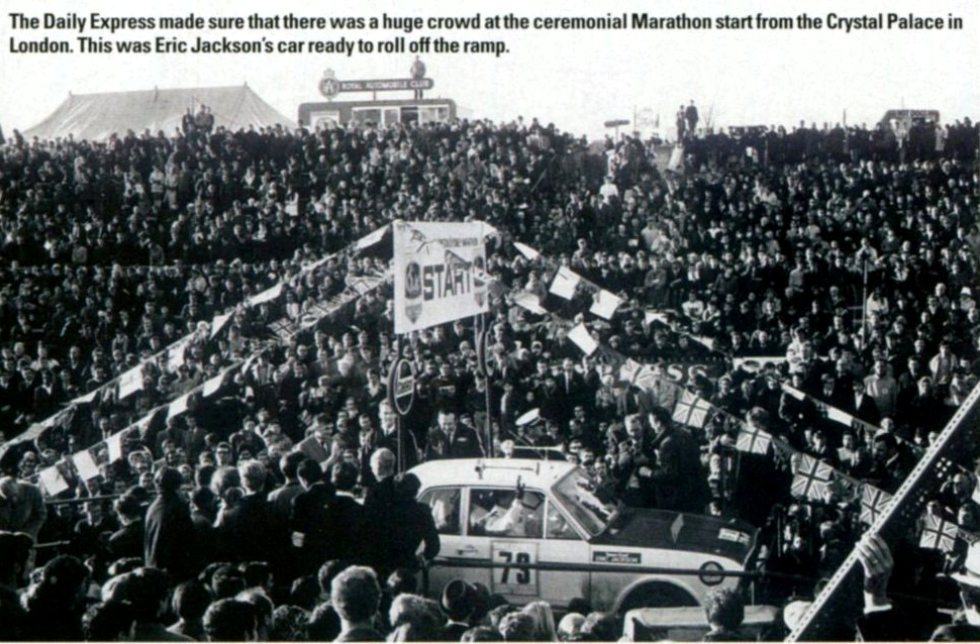

THE START

David Harrison continues with his discription of the event:

Sunday November 24th. A clear, sunny day and a good omen for the Marathon.

Crystal Palace was crammed with spectators, and we were particularly pleased to see trumpeters from the Regiment to “blow” us on our way. We were also seen off by the two little girls from Wath Central School, near Barnsley, who had “adopted” us for the rally. They gave us a box of home-made Turkish Delight which we promised to eat in Turkey. A promise we were very happy to be able to keep.

At last, 15.39 hours, we were away to a fanfare from our trumpeters. London was packed – no problem of route finding to Dover, just follow the crowd. One fond memory of London was being waved to by a policeman to go faster the wrong way down the bus lane over Westminster Bridge. Very satisfying.

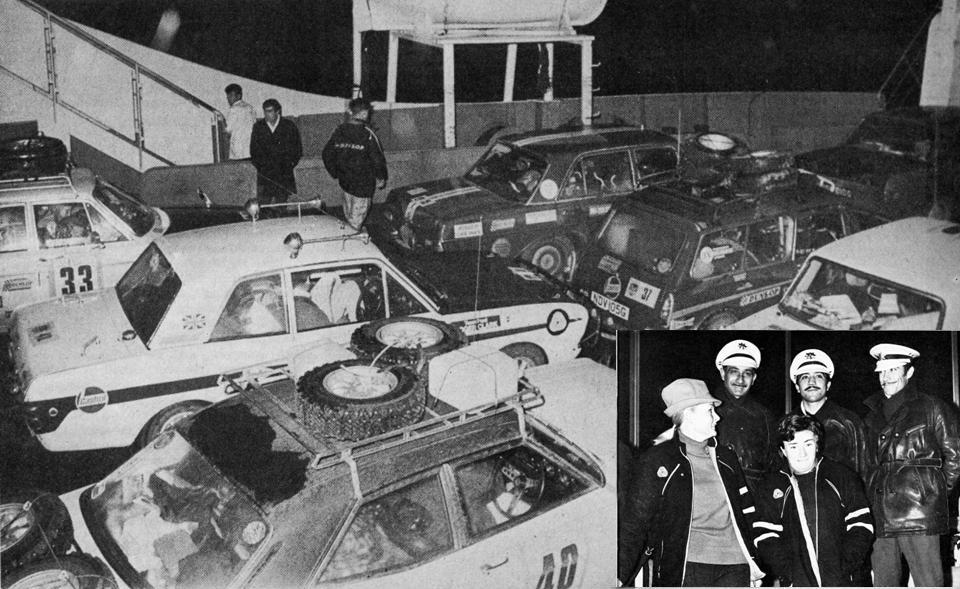

We booked in at the Dover Control on time and boarded the “Maid of Kent”, where we had the first of what turned out to be a series of arguments with waiters all along our route to Sydney.

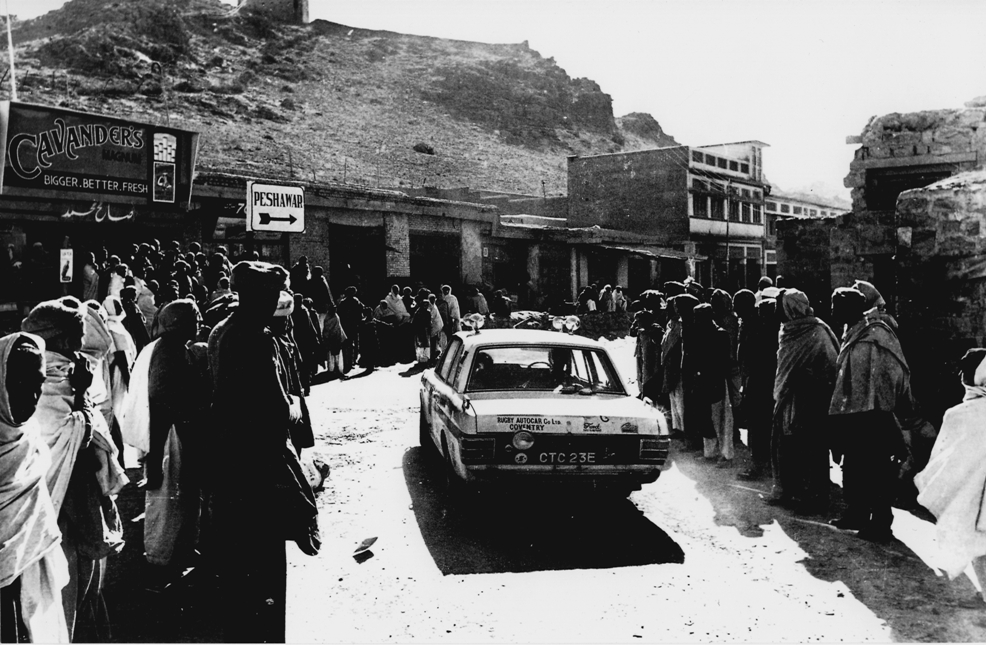

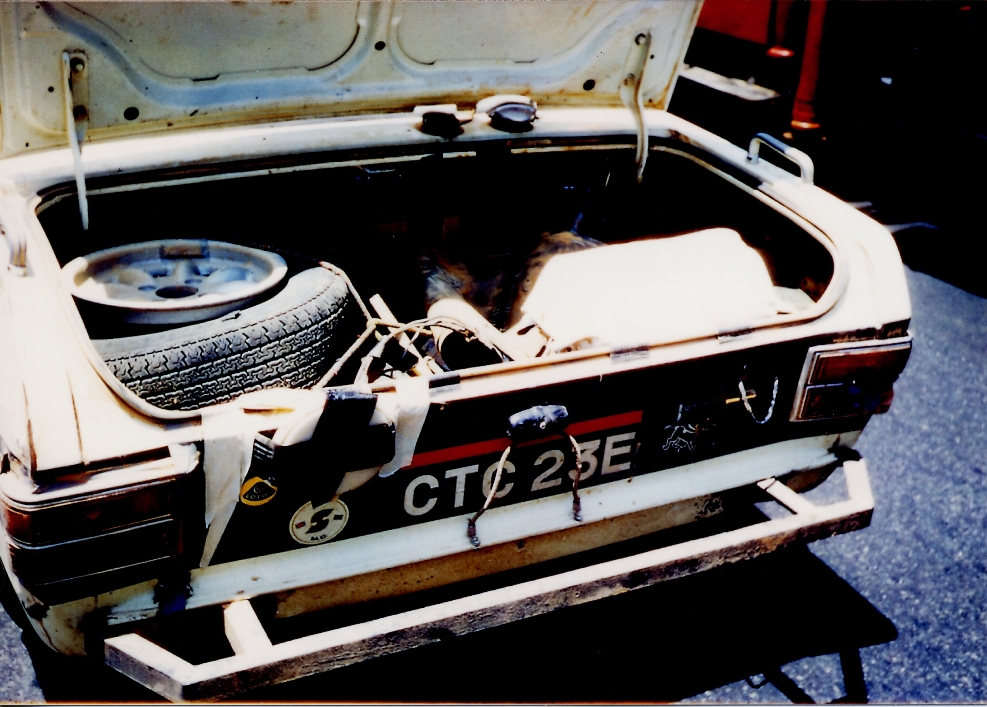

David and Martin (CTC23 E) alongside Rosemary Smith and Lucette Pointet (VPI 77)

Nick and Jenny Brittan (YVW 2 F) prepare for the off.

Roger Clark (VVW 506 E) gets going, and Bengt Sodderstrom (CTC 26 E) passes the Houses of Parliament. Eric Jackson and Ken Chambers still showing off their new wooly overalls, whilst the Tecalemit Lotus Cortina (JDR 456 F) follows a German Porsche that has been prepared to be able to roll all the way to Australia.

David and Martin make their way out of the London traffic

And we’re off!

EUROPE AND ASIA

Northern France was misty and to the dismay of many competitors the French authorities had closed the Autoroute to the Marathon. This did not deter most competitors though, and quite by accident we found ourselves following a French entered Citroen down the Autoroute to Le Bouget and the first Time Control.

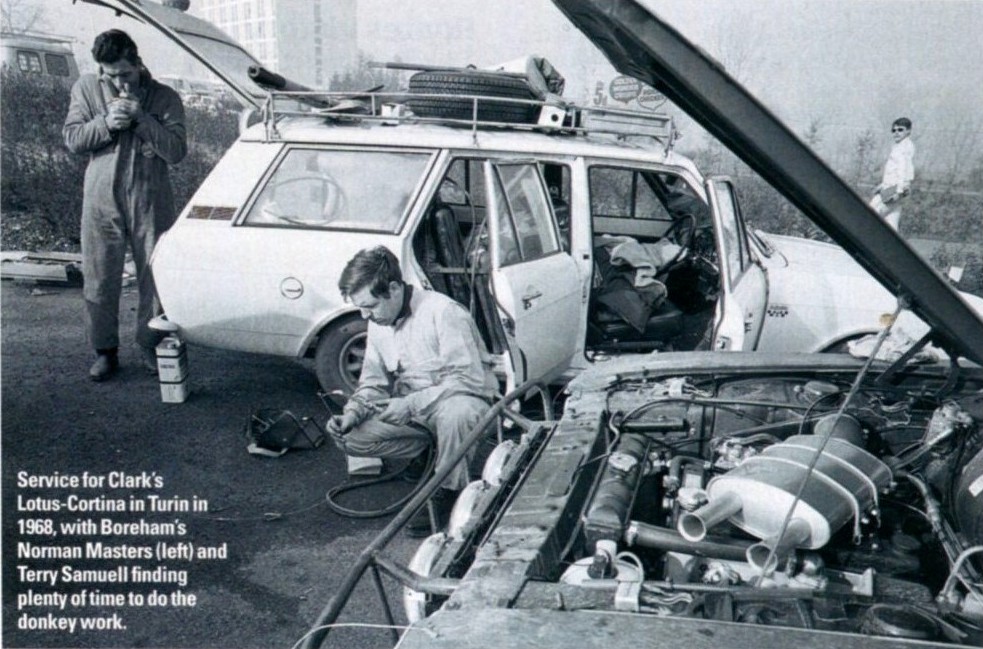

The car was running very well, but we were worried by a slight oil leak from the gearbox. We stopped near Mont Blanc Tunnel at a roadside garage and with a show of great enthusiasm from the ’garagiste’ checked the level. All was well so we pressed on into Italy and made a fast time to Milan Control. Here we met up with one of the Ford Works Service crews, but unfortunately there was nothing to be done to the car, so we went to the Motel for lunch – and our second battle with a waiter.. The Motel was taken over almost completely by Marathon competitors and we were most grateful to the guest who, unknowingly, allowed us to use his shower.

On from Milan to Yugoslavia and we crossed the frontier as darkness fell on the 25th. We had covered the first 1,000 miles and all was going well. Yugoslavia provided us with the first adverse conditions. It was icy and over the hills flurries of snow made the road treacherous. The road was well engineered and we had ample time so there was no need to take risks. By now we were into a routine of three hours on, three hours off. The driver navigated and the co-driver slept or rested. In a three hour spell it was unusual not to cover 180 miles, and 200 miles was frequently possible without taking chances. The car cruised at 85 – 90 mph over most road surfaces, and to Belgrade the roads were good. We reached Belgrade shortly before 6 a.m., with over 8 hours in hand, so the car was taken to the local Ford dealers where it was washed and checked over. We left the car at the dealers and went to the Hotel Metropole where we had a good six hours sleep followed by a large capitalist lunch.

After a moment of panic when the garage could not find our car key we set off on the next stage to Istanbul. By now it really felt as if the Marathon was in progress; some cars and crews were beginning to look tired and there had been one or two retirements. The team of four Russian Moskvitch cars appeared to have service points and support cars every few miles in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. They drove in strict formation, in order of seniority with a service car taking up the rear. All they needed were convoy flags.

Bulgaria was showing both official and unofficial enthusiasm for the Marathon. Border formalities were minimal and there were police or militia at all junctions urging the cars on. Despite the cold, large crowds assembled at towns and at junctions to see the cars. It was a remarkable experience. We nearly came to grief at one point in Bulgaria as we approached two particularly enthusiastic policemen who were waving their arms and jumping up and down. We gave them a flash of the lights and a blast from our roof horns and then we saw the closed railway barrier.

Rosemary Smith, focused.

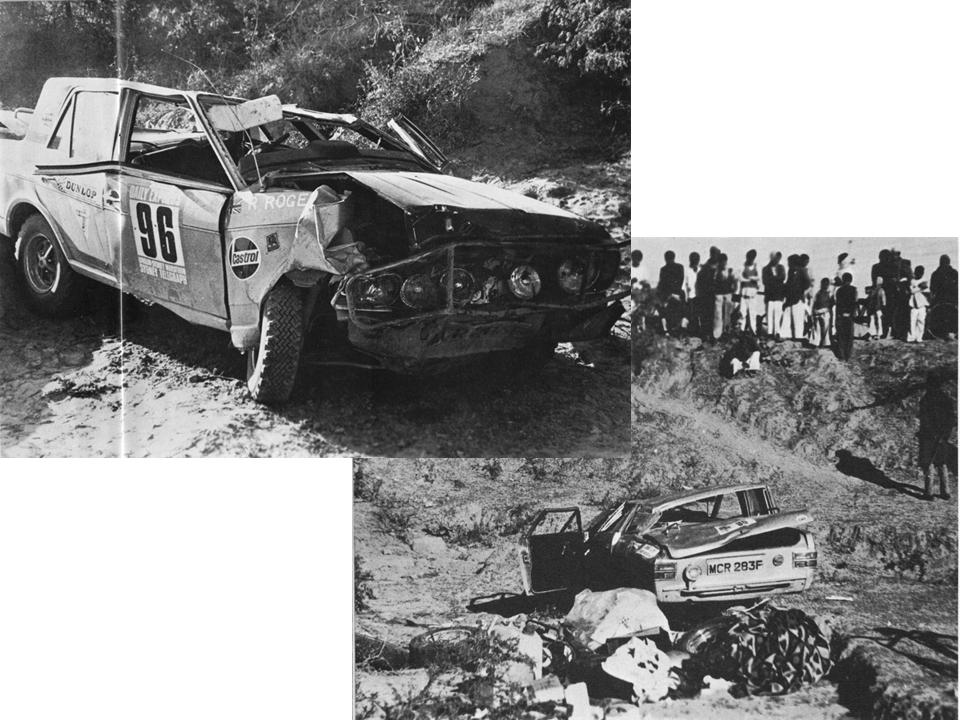

Bray, Sladen and Sugden come to grief, and their marathon is over.

We reached Instanbul with some five hours in hand and snatched an uncomfortable few hours sleep on a hotel lounge floor. We crossed the Bosphorus at dawn by ‘feribot’ and had our first sight of the Turkish lorry driver in daylight.

Roger Clark’s Lotus Cortina on the ferry. Rosemay Smith and Lucette Pointet being looked after by the Turkish Police!

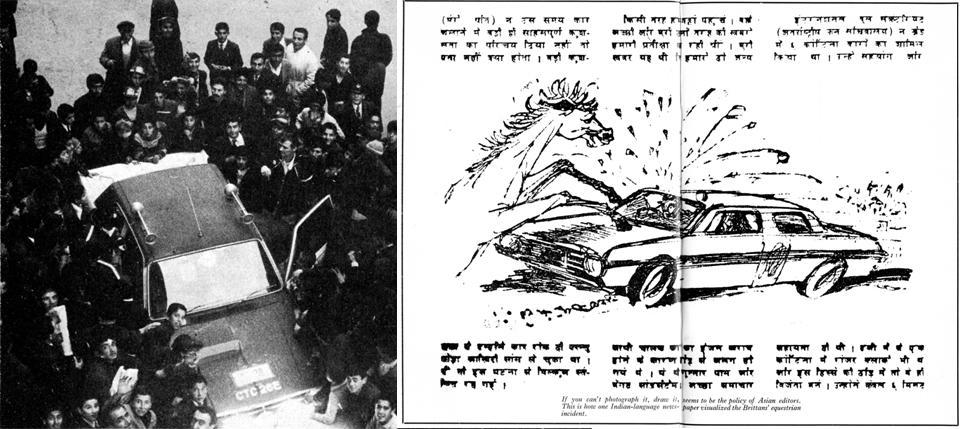

There is virtually no motor sport in Turkey, but every lorry driver imagines he is a budding Graham Hill. By the number of overturned lorries they have more imagination than skill. We passed one Marathon car some ten miles from the Bosphorus with the offside completely smashed – we slowed down and treated the lorries with increased caution. The town of Sivas, in central Turkey, was our next Time Control and the start of the first really difficult stage of the Marathon. We were allowed 2 hrs 45 mins. to cover 176 miles of un-surfaced mountain roads to Erzincan. Sivas did not inspire confidence. The town had turned out to watch the Marathon and hundreds of wild eyed silent Turks thronged the unpaved streets, crowding round the cars and being kept back by stave carrying police. Each arriving car was greeted with enthusiasm, and when Nick Brittan arrived in his Lotus Cortina with no windscreen and a damaged front – he hit a horse when travelling at 80 mph – the crowd was beside itself with joy.

Bengt Sodderstom / Gunner Palm in CTC 26 E had to retire with a blown piston at Sivas, donating their windscreen to the Brittan’s Cortina. The Indian press, in the absense of any photographs, drew the horse and Cortina incident!

The road to Erzincan was rough and slippery and the weather was not kind to us; it was raining. Only three miles from Sivas we came upon a right angle turn after a hump back bridge, and only by hard braking, followed by fierce acceleration, did we get round.

It is believed that sixteen cars went off the road at this point. The rest of the route to Erzincan is a blur of bends of all types; of climbing and descending; of crossing wooden plank bridges little wider than the car with nine inch concrete steps at each end, and finally a glorious seven miles downhill straight into Erzincan.

In Erzincan we checked the car, ate ‘compo’ curry with one of the BAOR support crews and replaced three lamp bulbs smashed by flying stones. Next stop Tehran.

The road to Teheran was generally good, but with long gravel surfaced stretches. We saw the dawn of Thursday the 28th break over Mount Ararrat and took a photograph to prove it. By now we were into our third time zone, and were 3.5 hours ahead of B.S.T. In order to keep the mental arithmetic to a minimum we kept one of our Everite watches on Local time and the other on B.S.T. All the rally timings were to B.S.T., and it was necessary to have one watch on Rally time1 throughout.

Teheran was pandemonium, and without doubt the most dangerous stretch so far. The traffic volume was enormous and everyone drove with little regard to lane or direction. Particularly intrepid were the Vespa taxis which appeared apparently from thin air in front of our bumper. We were given a magnificent reception in Teheran by the Phillips Electrical Company, and we had a good meal and a much needed shower while the car was being checked over. We had now covered 3,600 miles in four days and the car was in excellent condition. All we had needed to do to the car was put in three pints of Castrol. We were brought down to earth a little in Teheran when we were reminded by Henry Taylor, the Ford Competition Manager and our Team Manager, that we were just over halfway to Bombay.

What was thought to be the most gruelling section, to Kabul, lay ahead. Only 25 hours were allowed for over 1,500 miles, almost half of it un-surfaced. We set off hoping to keep up with the average, and by the Afghanistan border, with the worst behind us we were only 20 minutes behind our schedule. The car took the pounding of the potholes and corrugations magnificently. All the hours spent preparing the car seemed worthwhile.

In the 600 miles to the border nothing came loose, nothing broke. We were very pleased.

The Iranian/Afghani border crossing was a masterpiece of diplomacy. At the end of a red carpet sat Marathon Officials and the chief Afghani customs and immigration officials. The border crossing which took recce crews up to 24 hours took us less than a minute. All this in the middle of a desert, more than 60 miles from the nearest village.

At Herat, 100 miles into Afghanistan, we met the Ford service crew who had flown in from Teheran. Here we were asked to stay in company with one of the other Ford works cars, that of Rosemary Smith and Lucette Pointet, to Kabul. Their car was missing on one cylinder and the engine could have broken at any time and Afghanistan is a wild country to break down in. Because we restricted our speed to that of the sick car we lost over 3.5 hours getting to Kabul, but it was worth it, because temporary repairs were made to the car and it reached Bombay, and eventually Sydney.

Kabul was bitterly cold and we were glad we had remembered to put antifreeze in before the start There was a compulsory halt at Kabul and we managed to get a few hours sleep before tackling the Lataband from Kabul to Sarobi. This pass was expected to be impossible to cover in the tine allowed, and apart from being dangerous, was a potential car breaker. The authorities however had stepped in and put a grader over the pass to level it, to the chagrin of the organisers and the delight of the competitors.

Friday 29th was a glorious day. We left Kabul just before dawn with 1 hour to reach Sarobi, 42 miles away. The road – and that flatters it – twisted its way up the side of gorges and plunged down again. Coming round corners into the blinding sunshine knowing there was an unfenced drop of goodness knows how many thousand feet only yards away is an unforgettable experience, all the more so as this was the Hindu Kush, not the Alps. The grader had moved many of the really big rocks, but the Surface’ was frequently 4-6 inch diameter stones, and dust. A hundred cars at speed, even at minute intervals, put up a lot of dust, even seeing out was a hazardous business. Despite this Martin managed to take photographs while hanging on to the navigator’s seat. He said the pace notes were too difficult to read. We were only fourteen minutes late on this section, and were very pleased because the fastest car lost five minutes.

From Sarobi we soon crossed into Pakistan, to be met by the most delicious cup of tea served to as by the Pakistan Army Electrical Mechanical Engineers service crew at the border. They were delighted to see us and could not have been more friendly or helpful. As we set off down the left hand side of the road it was almost like being back in Britain.

We were soon through Pakistan and into India. This crossing, which was expected to be very ‘sensitive’ was another example of first class international co-operation. One official said to me “This Marathon has done more for Indo-Pakistan relations than the United Nations has done in fifteen years”. As soon as we reached India it was apparent that the road, not closed to other traffic, was virtually ‘out of bounds’ to all the Marathon cars. The bullock carts and lorries were almost non-existent, and we thought this was going to be the easiest stretch so far. We did not allow for the people.

At Indore over 5 million people along a ten mile stretch of road watched the Marathon go past, and every one of them wanted to touch the car or its crew. It was a frightening experience as the cars slowed to walking pace and were swamped -by people. They sat on the bonnets, roofs and boots, hung on door handles and horns, and occasionally put their toes under the wheels. At one point the car in front stopped suddenly to jerk spectators off his boot and we drove into the lack of him. Fortunately he was one of our team, and our ‘rooguard’ coincided exactly with his rear crash -bar. Two minutes later the car behind us drove into us – again no damage. There is a lot to be said for crash bars!

The Indian Army had arranged service and repair points along the route, but fortunately we had no need of them. They were also producing food parcels for some of the Army crews. We passed one sign saying ‘Major Preston, your lunch box 200 yards’ and in 200 yards was a table with a white cloth and two soldiers waiting for Major Preston. That really was service.

We reached Delhi in good time and had four hours sleep in a hotel. The crowd at the control was enormous and almost out of hand. When we set out a few hours later the car had lost many of its advertising stickers to souvenir hunters, but nothing vital – like lamps – had gone. Delhi to Bombay was a long hot and sticky drive, the crowds were as vast as ever, and all seemed convinced the Marathon was a race, and we were urged on to overtake the car in front.

The Alec Sheppard / Ronald Rogers Cortina 1600E after somersaulting down a railway embankment near Agra and the Taj Mahal. None of the Lotus Cortinas were fitted with roll bars either, and these pictures show just how dangerous the marathon was. Neither Alan nor Ronald were badly injured.

We reached Bombay with over six hours in hand and cleaned the car from top to bottom – cleaning out the Asian dust ready for the Australian variety! The car was serviced – the fifth pint of Castrol since leaving London put in – and additional wire mesh protection put over the spot lamps to help protect them from flying stones.

With 15 minutes in hand before we checked in we started up the engine, and a high pitched scream came from the alternator belt. The alternator had seized. Mechanics descended on the car and the alternator was changed and checked. All was well so we drove flat out through the darkened streets of Bombay to the control – 21 minutes late after being in Bombay for six hours. Never mind, we knew the car was in excellent condition for Australia, and this would be the really testing section.

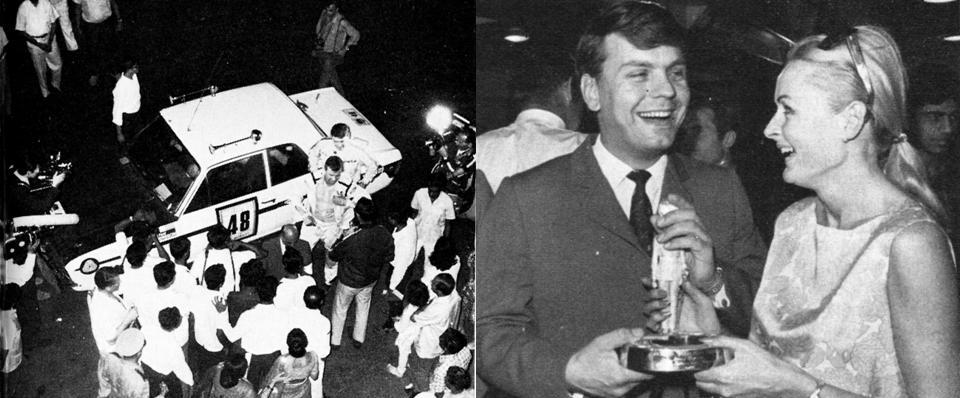

Roger Clark was leading at Bombay in his Lotus Cortina, and received the Guards Trophy and a cash prize. Roesmary Smith seems to want the trophy as well!

In Bombay we were entertained by the local Gunner unit who lent us a jeep and driver for the duration of our stay. They also gave a cocktail party for us – in prohibition conscious Bombay.

We boarded the P & 0 Liner, Chusan, on the 4th of December and enjoyed the festivities and relaxed attitude on the ship. We spent one evening ashore in Colombo where we were entertained by the Colombo Motor Sports Club.

After three days of rough seas the weather again calmed as we entered Australian waters.

AUSTRALIA

Martin Proudlock picks up the story for the Australian leg:

Friday the 15th dawned clear and fine. The Chusan berthed at Freemantle in the morning and we finally cleared customs and immigration by mid-day. The afternoon was spent rechecking maps and hoping that the car would get through its police inspection without any faults. In the evening we collected the car from Freemantle and drove in convoy to the trotting track in Perth where the cars were lined up in the order they were due to start next day.

On Saturday morning there was a conference for all the Ford drivers to go through the route and learn the servicing plans laid on by Ford and Goodyear across Australia. The final hours were a rush, doing last minute shopping, packing and hoping we had everything that we might need.

Roger Clark, leading the Marathon, starts the Australian leg in Perth.

Our start time was 4.30 p.m. local time, and immediately after leaving the stadium we drove to the Ford garage where the car was given a quick going over by the mechanics. The tyres were changed and water and petrol taken in. The car had been in ‘Parc Ferme’ since Bombay and we had been unable to do any of the final checks on it. Thirty minutes later we were off to Youanmi, 340 miles away, which used to be a mining town but all that remains now is a crossroads. This was a fairly slow section as we were driving through built up areas. The road surface changed to gravel 250 miles from Perth, and 15 miles later we saw our first kangeroo, 5 miles from Youanmi we saw our second. We did the first three movements of a square dance with it and ended up hitting it on the front right hand side. There was a large ‘crump’, some flying glass and a ‘Roo with a headache. We had hit him at about 45 mph and didn’t stop. At Youanmi we inspected the damage. One broken spotlight and a slightly bent ‘Rooguard.

Youanmi that night was a like a small town with farmers and inhabitants from 100 miles around having barbecues and parties. We had an hour in hand and spent most of it talking to a farmer who was making the most of the occasion.

The next section to Marvel Loch was to be the first of the many fast rough sections. We had 4 hours to cover 245 miles. The time interval between cars in Australia was three minutes to allow the dust to settle. As we started from the control the car before us, leaving late, roared past.

We followed blindly in his dust at 50 mph. 12 miles later we managed to overtake him when he stopped in a farm-yard. David shouted ‘Left, right of the house, left right through the gate’ and we were past. The road on this section was, for the most part, one tracked with trees and scrub close on both sides. Overtaking was difficult to say the least because of the dust and not being able to see where the road went for more than 100 ft ahead.

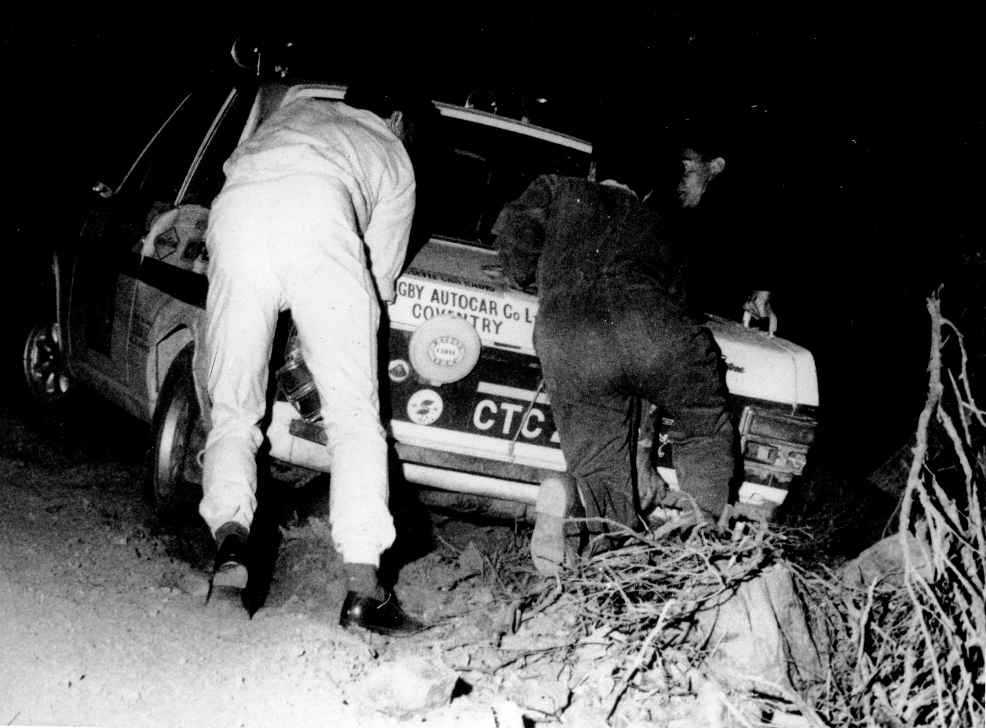

Our second mishap occurred where there were a series of wiggles in the road. We caught a tree on the left hand side, bounced over to the right, corrected too hard, went clean through a large bush on the left hand side, straightened up in the centre of the road and accelerated back up to 70. 10 miles further on we came across a left hander not marked on our notes and ran off into the scrub on the right. With the aid of some photographers who happened to be standing there we bounced the car out. Inspecting the damage we found the left hand side, from the door back, flattened. One ‘Desmo Boomerang’ wing mirror glass broken and half inch diameter piece of wood, which had pierced two layers of PM, resting gently against the relays for the lights. The right hand wing mirror was snapped at the base, but apart from that there was not other damage. We continued on and reached Marvel Loch where we re-fuelled and changed tyres. We lost 4 minutes on the section.

Next, another difficult section to Lake King, with 120 miles to cover in 2 hours on tracks that twisted between trees and went over rock outcrops.

Dawn was breaking as we set out. All being well by late that night we would be on the other side of the Nullarbor Desert, but first the section to Lake King, described in our route notes as ‘The first 70 miles of this section are fairly fast but then it gets more and more ridiculous’! We twisted and turned and slid for two hours and were pleased when we reached the end, losing only 20 minutes. A quick drink of orange juice from the locals and a change of drivers and we were off again.

Inspecting the damage from the previous night.

The next control was at Ceduna 901 miles away and we had 15 hours to do it in. At Noreseman we changed back to high speed tyres and set off for the Nullarbor itself. We drove for about 200 miles and changed drivers and so on throughout the day. Luckily there was a cold front coming across Australia with the rally, and the temperature was only about 90f – 100f as opposed to 120f -150f. The first 300 to 400 miles were through blue gum trees and open scrub country. There were obvious signs that there had been forest fires in the past and the trees looked dead from the top branches downwards. The next 200 miles were through more scrub and open countryside. There was very little sign of any wildlife, and little sign of human habitation. Petrol stations were every 150 to 200 miles. Back onto the dirt roads for the last 300 miles. At times we wondered if it would ever end. Dusk fell and dodging the potholes became more difficult. On the dirt surface the car threw up considerable quantities of dust, a lot of which found its way into the car.

We arrived at Ceduna with an hour and a half in hand. A shave, shower and steak dinner at a motel did wonders for us. The car by now had a good layer of dust all over everything. The air conditioned Australian Holden’s on the other hand were spotless.

The next section to Quorn was all fast tarmac, and we had orders to make up as much time as possible to enable us to have a major service at Port Augusta before completing the final 1,500 miles. We arrived in Port Augusta at 3 am to find the Ford mechanics working flat out to put the Chambers/Jackson cylinder head onto the Clark/Andersson car. It was a race against time as Roger was still in the lead at that point. We had a few of our dents knocked out and, as a precaution, new front suspension legs put in.

We set off again, after a break of a couple of hours, for Quorn 10 miles away. It was a wonderful dawn and we were about to go through some of the best scenery in South Australia. The first section turned out to be easier than anticipated. We had time to have a cup of coffee before setting off on the next section, which was expected to be the worst in the Finders Range; 75 miles in 90 minutes was the target.

55 miles later coming over a left hander we went straight on into a large ditch. The car stopped within its own length from about 45 miles an hour. We thought we were out of the rally when we first inspected the damage. The front right hand wheel had pushed the bulkhead back an inch or so, the starter motor connections were snapped beyond repair, and the windscreen had come half out in one piece. The right hand side had been pushed back about an inch; enough to stop the door from opening properly or locking shut. Despite being tightly strapped in, which must have saved a few broken bones, the steering wheel was bent down. David set off to a Passage Control about 5 miles away to get help; within fifteen minutes he was back with a dozen helpers. We towed the car out of the ditch and set to work on the front wheels. We jacked the car up and with an Australian car acting as anchor, pulled the front suspension forward by attaching it to a passing Toyota Land Cruiser that we stopped. Some quick aligning by eye and we were away. Altogether we lost 2.5 hours over the section.

From Brachina the route was to Mingary described in the route notes as ‘possibly the worst section in Australia’, with 210 miles to do in 4 hours 10 minutes. Luckily all the 43 gates on the section were open. We set off to do the section with our fingers crossed, hoping that the front end would hold together. This section was certainly the most uncomfortable one physically. Daring the heat of the day we drove through loose sand, ruts, streams and more sand. It was the only occasion during the rally that the electric radiator fan switched itself on. Added to this the driver’s window could not be closed fully and the inside therefore received more than its normal supply of dust. Somehow we made the section without losing further time.

Shortly after leaving Mingary we crossed into New South Wales. Throughout the afternoon, evening and night we drove South East through Menindee, Gunbar and several other towns, a mixture of tarmac and dirt, driving as fast as possible. Where possible the navigator slept. We stopped for a meal at about 10 pm. and this refreshed us a great deal. The car was going extremely well except for a knocking sound coming from the engine and we now had only 800 or so miles to go.

In the early hours of the morning we again met up with the Ford service crews. They quickly checked over the car, but were unable to diagnose the knock in the engine. We were advised not to take the engine over 4000 revs, about 70 m.p.h.

Dawn on the last day was breaking as we drove into the Australian Alps. On one section we drove up and up following an Electricity Board track. There were steep drops to the right and left of us. Driving by now was a mechanical action as bends of every angle to the left and right, going uphill and down, appeared before us. We pressed on with the aim of sparing the car and getting to Sydney. We had up to12 hours lateness before we would be deemed retired. It was to be a long day. Dawn at 4-30 a.m. and we knew we would not be at Warwick Farm much before 6:30 p.m.

By now sleep was a luxury we could not afford, as in some places we needed four eyes for driving. My recollections of that day are bends and more bends with drops first on one side then the other as we crossed and re-crossed mountain ranges. There was a good tarmac section between Ingebyra and Numeralla and then it was back into the hills again for the last two dirt sections of the rally. 5 miles from the end of the last one we had our one and only puncture. Then it was tarmac and a matter of 80 miles to Warwick Farm, the racing circuit, outside Sydney,

We arrived at 6.50 p.m., with the car looking a bit bent and somewhat dusty, the crew equally as dusty but delighted at having made it and being placed 30th. We stayed that night near Warwick Farm and the next morning drove in finishing order into Hyde Park in Sydney where all competitors were surrounded by hundreds of spectators looking at the cars and asking questions.

We spent two days in Sydney and flew back on Friday 20th December in time for Christmas.

c

The car looked a little worse for wear when parked up in Sydney!

What Happened to the Cars?

The easy one first! VPI 77 was returned to Ford Ireland, who subsequently sold it off. It was bought by Cal Withers, who ran it in the 1970 London-Mexico World Cup.

I was contacted in December 2020 by Richard Apsimon, who bought VVW 506E (Roger Clarks car) in 1973 from an advert in Motoring News. This car had been returned to Boreham after the event, presumably to take it apart to analyse the strengths and weaknesses of the Mk2 Lotus Cortina. They sold it on to a chap in Essex, who subsequently sold it to Richard via Motoring News magazine. Richard sold it to ‘a garage in Gloucestershire’ in 1979, and there the trail goes cold.

I was contacted in May 2020 by Ron Page from Australia who owned YVW 41F (Eric Jacksons car) for quite a while. When the Marathon finished, the remaining Lotus Cortinas were left with Ford Australia, who subsequently painted them red and ran them in the national local rallying events.

Ron says that Ford had 3 cars after the Marathon. Two are without doubt YVW 41F and CTC 23E ( the Army car), but the third one is not certain. Ron thought it may have been VVW506E (Roger Clark’s car) but we now know that came back to Borham after the event. That leaves CTC 26E (Bengt Soderstroms car) and YVW 2F (Nick Brittans car). As CTC26E retired in Turkey with a blown engine, it is possible that it could have been that car, maybe shipped over to Australia for ‘parts’ for the other cars? YVW 2F had an accident in Tukey and had a bent front end, although it continued after a windscreen was donated to it from Bengt’s car. It then had a 2nd accident near Tehran, which put it out of the rally. With the front wheel up against the rear of the inner wings / bulkhead, it would have been a bit more difficult to get this car over to Australia, but not impossible.

In any event, the cars went on to acquit themselves well in the Australian Rally Championship in 1969 run by the Ford Australia team, and in 1970 one car continued to be at least affiliated with Ford, and the other two were run by privateers in rallying and rallycross events.